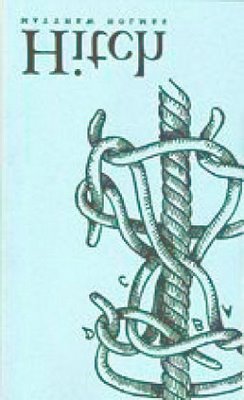

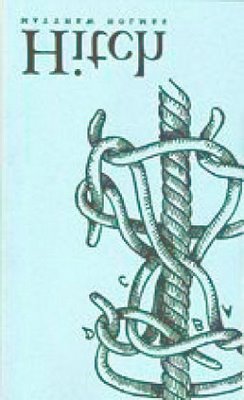

Matthew Holmes' Hitch as a Broadside Ballad

Now, here's a curious thing: a book, no doubt about that, beautifully printed, for sure, cleverly designed and manufactured to look like a book from the anti-book tradition of Canadian poetry publishing.

Matthew Holmes, The Virtual Reality Version

Hitch.Nightwood Editions, 2006, 96 pp., $16.95

A fine example of an early 21st century technical writing manual,

with close-up diagram showing the procedure for linking the nerves to the spinal cord.

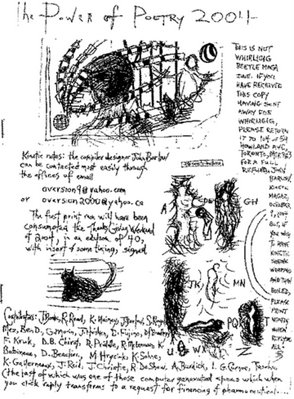

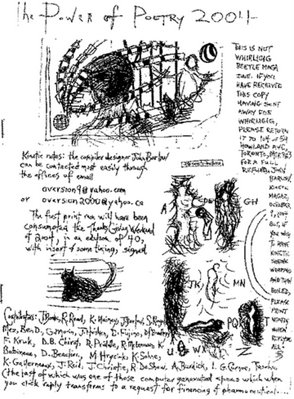

Highlights of the Canadian anti-book tradition include the Gestettner of the TISH poets in 1963 Vancouver, the purposefully badly photocopied and/or elegantly designed poetry books of the anarchist tradition of the Toronto Small Press Book Fair, and mail artists bent on distributing work without either art or a book.

John Barlow's In The Power of Poetry

And that's just the cover!

The sleight of mind that can even conceive of such a challenge is the very definition of being Canadian — living as we do in a country that prefers to read books from other countries and has few places to sell those from our own, and all in all sees this as the ultimate in sophistication.

Oh, wait. That's not Canada. That’s almost everyone.

A little evidence to that effect:

Barlow's (and Holmes') kind of publishing as the true act of a free man has, it seems, a long history.

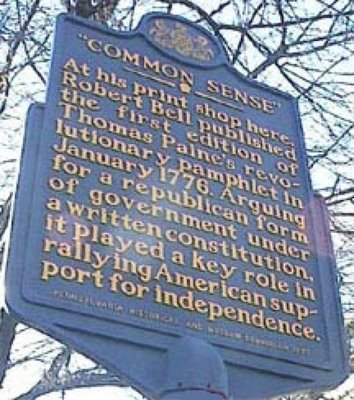

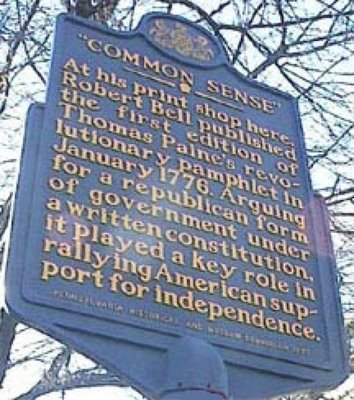

Thomas Paine, the Final Draft

I suspect that what Paine had in mind with his title, Common Sense is not what we necessarily mean by it today, as something reasonable and obvious to all men without the application or corruption of intellect, but something akin to Common Law, as in from the people, not from their lords and masters.

Now we use it to describe the cohabitation of a man and a woman with the sanctifying blessings of (and obligations to) the Church. Nice!

Other definitions of the essence of being Canadian:

Oh dear. But, you know, meaning is a slippery business, after all. You just can never nail it down to one thing or another. I mean, like all good books, of course, even Paine's Common Sense had earlier drafts. Here's a sample of one of its earlier evolutions:

California Quail

Well, well, well, leaving aside the notion that Canadian anarchist publishing was American-inspired, anarchist publishing was the kind of thing that in the 1960s gave us Canadian literature as we know it today, with the gliterati at the Gillers in all their new dresses and black suits and the writers sitting around in their v-neck sweaters wondering what they are doing there. Back then it was just samizdat.

Illegal books, illegally typed by hand, and illegally distributed in Cold War Eastern Europe. The kind of thing that could get you hurled into the Gulag.

You ever wondered what happened to samizdat? Simple. The American version has become a point of pilgrimage for the tourists of Revolution.

The Final Draft of Thomas Paine's Common Sense

Abbreviated for instantaneous transmission along the imagistic cortex

An example of American Anarchist Post-Gutenberg Publishing.

The Soviet version has become a point of pilgrimage for the tourists of Revolution.

Russian version of the Toronto Small Press Book Fair.

Samizdat museum in the former Soviet Union.

What was forbidden is now a shrine.

Crowded, too!

(Note for Pilgrims: follow the Light at the End of the Tunnel)

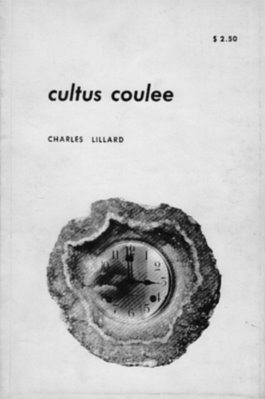

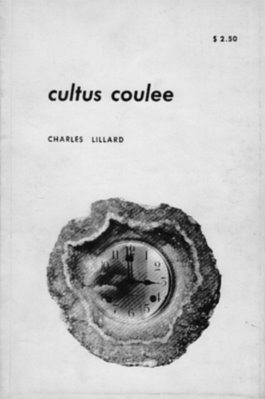

In fact, Sono Nis Press even did a series of samizdat books back in 1971: imitations of the books privately printed on typewriters and passed out by hand at great peril in Soviet Europe.

For the most part, the poets published in the series were graduates of the Creative Writing Department at the University of British Columbia, back in the days when the department was not the establishment, but was trying to throw paper airplanes over its walls.

Charles Lillard’s Cultus Coulee

One of Sono Nis Press's Samizdat Poetry Series

Check out the funky retro courier font, typed on a typewriter for sure, in Andreas Schroeder's version, file of uncertainties below. Just the perfect thing for Matthew Holmes, what with all the tricky rope work and all.

35 year old typing by Andreas Schroeder

In the Soviet Union, of course, publishing in samizdat could get you into the Gulag. And back in non-aligned British Columbia? What about that? Back in the days when the entire Hungarian forestry department was ensconced at the University of British Columbia?

Na. The peril wasn’t there. I mean, these were poets, sure, so they were rather unwanted social accidents, granted, but they were British Columbian poets, which is to say they felt like they were on the right side of the Rockies, and they were Canadian poets, which is to say they were just as good as creating virtual realities for themselves as they were at writing poetry.

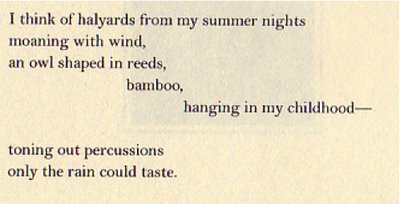

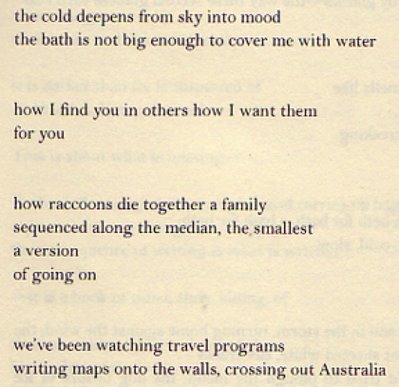

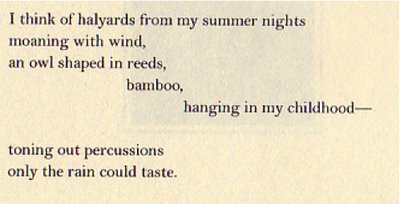

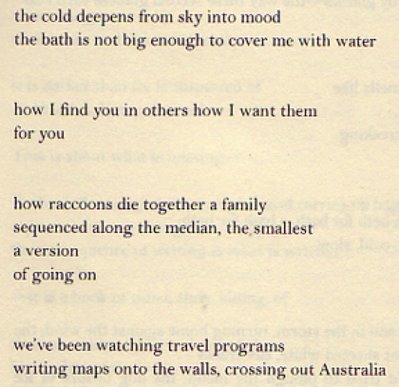

Here's a piece of virtual reality from another and very distant Canadian coast, from New Brunswick:

A few bytes of holographic code

for the re-creation of the world of Matthew Holmes inside your head,

from Owl Shaped in Reeds

Hey, what's that peeking in from the other side? Check it out.

Collector’s Card Version of Matthew Holmes

Useful, too!

(Note for Travellers: It remains unclear whether these rooms come with private bath,

or whether you have to share the w.c. down the hall.)

See what I mean? Mail art between covers. Absolutely everything is in there. It seems to be Holmes' desire that they all cohabit in there.

How common!

Back in the 1960s, everyone was getting in on this act. Fiddlehead Books in Fredericton, New Brunswick, just published everyone who sent them a manuscript. So did bill bissett's blewointment press in Vancouver. He rejected no one. Of his writing in that time, bill says that he was trying to change the world. And, sure, production standards in this genre were, well, low, but the craziness of the environment was invigorating. Invigorating is good.

Illustration from Marilyn Bowering's The Liberation of Newfoundland

published by Fiddlehead Books in 1973.

Then came canlit.

IKEA moved into the country and sold knockdown beds cheap.

Time passed.

Past time came again.

Past time passed.

Everyone forgot everything. Everyone slept in.

People, understandably enough, started to get pissed.

Starbucks came onto the Canadian scene, to wake everyone up.

Then all the writers of Vancouver started to haul their laptops to Starbucks and write from there, so they could get away from it all and (in a writerly way, of course) rub shoulders with people.

Then Matthew Holmes started to send out his messages, in code, to show there was still life out there. You know, it's nice to see the original craziness honoured in Matthew Holmes’ first book of poetry, Hitch, put out by the resurrected Blewointment Press and made to look like something run off on a photocopier that somehow learned how to print beautifully, full of objects made to look like poems, and presented as a combined guide to semaphore and knot-making.

A Sample of Matthew Holmes' Doing his Houdini Act

from Traditional Dances for Tourists

A nice nod to Fiddlehead, don't you think?

Oh. Hitch comes with a warning, though: if you squoosh it down too long in your scanner and hold down the lid, the pages will never close again. Yeah, I know. Everyone's using cheaper paper these days.he

Pretty soon, poetry will have folded itself down into origami.

It's like listening to something by the American composer of silence, John Cage, or by the Canadian composer of solitude, Glen Gould.

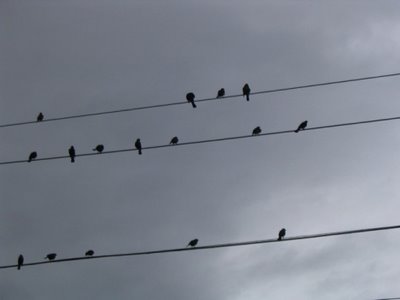

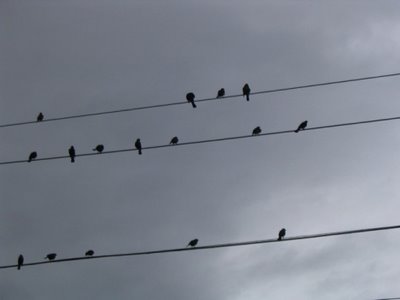

Starlings in the Blenkinsop Valley,

Of course, all these nods to the past, all this mail art and powerline art, has to have a root somewhere, in more than the question, saucily put: Which came first? The blackbird or the egg?

Well, forget about making love in a canoe. A modern street balladeer is someone who knows how to wear armour. In some cases, it might be furnace ducting.

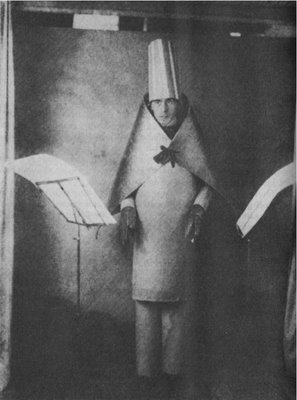

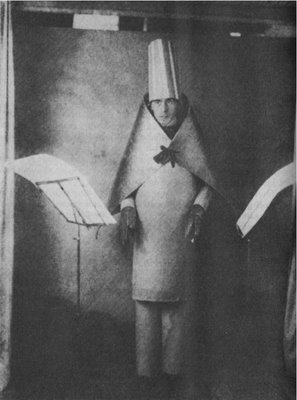

Hugo Ball Dresses Up Like the Tin Man

to read a nonsense poem in Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich in 1916,

while WWI was raging not all so far away.

Expecting tomatoes, are you, Hugo?

In other cases, it might just be the covers of a book.

Want to get away? Just let the pressure go.

Come on, let it go. Breathe in. Breathe out. Ahhhhhhhh. Feels good, huh? Remember:

Matthew Holmes lets the pressure go, but it's a sly sleight of hand, built on humour. Hugo Ball didn't mind a little bit of humour, either. Just getting up in front of a crowd was funny enough for him.

You see, both Hugo and Mathew stand at the end of a long tradition of street balladeers. Well, past the end, actually, because, really, they can only reference something that has gone. There just aren't any street balladeers anymore.

That's what we have the magazine racks at the grocery store for, come on.

No poets, either, actually.

But, here's the miracle: I once ran into one in Toronto. The year was 1998. The summer was hot and muggy. He had a tray strapped in front of himself and was selling poetry: USED DOG URINE.

Well, that's what his sign said. The poems were photocopied on bright, yellow paper.

It was like seeing a Great Auk.

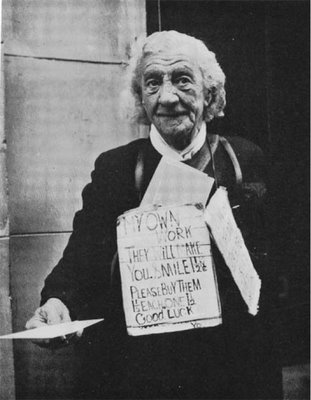

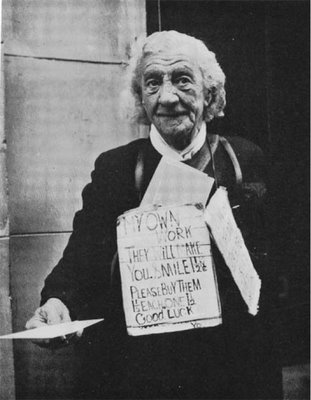

Kind of the Canadian equivalent of this English Dude:

Street Bard in London.

Hmm... don't you think he looks a bit like Robert Graves?

That’s what poetry will do to you.

The damn stuff will kill you in the end.

Graves ran his own printing press, too, but that was on Mallorca, where he had gone to put England behind him, and where he published beautiful, artistic volumes of poetry for an elite market.

Kind of like this:

The Poetry Book as Fetish Article

Hitch Yourself to Hitch Right Here Today.

Except, of course, this isn't Mallorca, it’s Canada, in 2006, which means that, in the true schizophrenia of Canadian society, playing the cute American game of privileged elites pretending to be defending the rights of common law, while Matthew is trying to remake 1967, other people are trying to remake this:

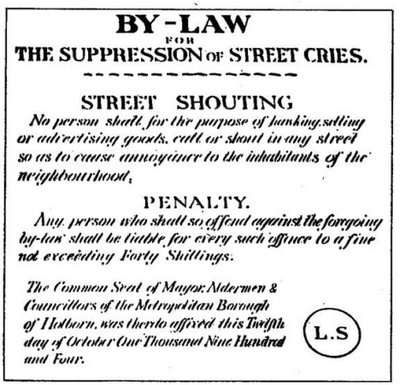

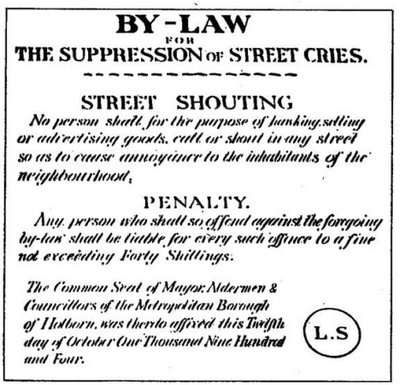

English Bylaw meant to stamp out street ballads once and for all.

That’s the context Matthew Holmes is writing in. Everything you learned (or experienced) about the development of society in the 20th Century? About the bloody battles that eventually handed power to the people from aristocratic and intellectual elites?

Well, that’s over.

It just doesn’t apply any more. All we have are ruins, and in those ruins, young poets like Holmes are left trying to create a world, a poetic, out of the shards. It’s all shards. Everywhere you look, there are shards: shards of sestinas and shards of sonnets, shards of language poetry and shards of visual poetry, shards of modernist free verse and shards of Gray’s Elegy on a Country Churchyard, all smashed up and lying somewhere on the tundra. The gig is up. The poetry is over. Now we have Canlit. Now we have Carmine Starnino railing against Canlit, in this 'art' learned at school.

Whereas the real poetry was meant to act upon the world. Kind of like this.

What looks like a photoshopped poster of contemporary politics in Palestine.

See what I mean?

The thing about reality is that it doesn't exist anymore. It, too, went the way of the Great Auk. The thing about street ballads is that they were the refuge of the working class. This was their art. Silencing them was more than an aesthetic statement.

It was politics.

So, how on earth, then, did some of it survive for Matthew to reference and within the context of poetry-as-an-aesthetic-object write a virtual street poet experience?

How did such a fragile thing survive, so late past history, for him to nod to, and how did there survive enough readers familiar enough with the weaker points of the new genre to get his joke?

Well, let me suggest it was these guys who smuggled it through:

Street Balladeers at Oktoberfest.

That’s the playwright Bertolt Brecht, second from the left.

The poets might have been complicit with modernism, but the dramatists were not. In fact, they were trying for a little bit of improvisation, gently and not-so-gently testing and probing their audiences. Here is one of the twentieth century's greatest dramatists:

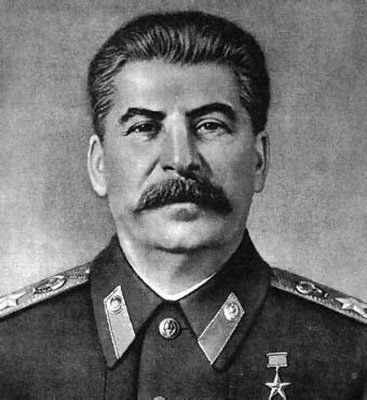

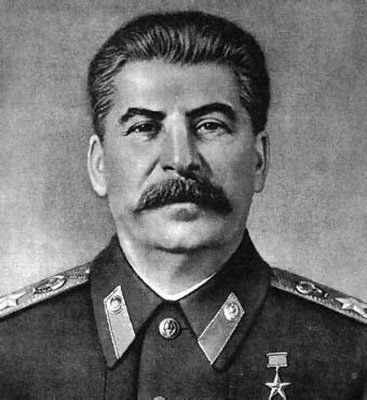

The Dramatist and Impressario Josef Stalin

(Note to Conspiracy Buffs: Notice how he is losing his head in his role)

Stalin was really keen on spectacle and on audience participation. It was his aesthetic stance that the audience members were, in themselves, nothing, that the individual human experience was an illusion. Collective experience, the experience of an audience also playing the roles, was all. The brutality that can come out of such an aesthetic has, of course, caused it to have some pretty nasty reviews. After all, it's not the job of a playwright to enslave or even kill his audiences, but to hound them out of the theatre and into the streets.

Where, of course, society forbade them to sing their ballads.

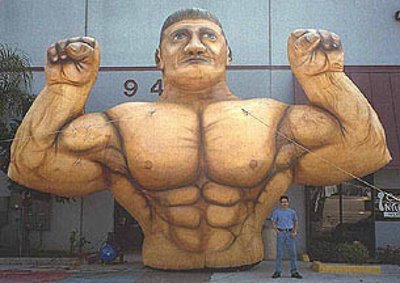

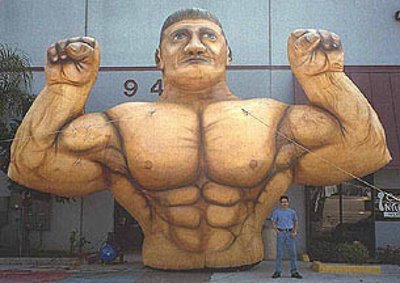

Nowadays, a strong man is someone you blow up with hot air.

I think Brecht would have liked that.

Man and his Ego

Circus strongman as an advertising gimic.

The tradition of a free peasant class, untramelled by art, was, however, not doing very well in Brecht's time, either, in the 1920s when the picture of his comedy troupe was taken, but had far, far older roots. If history has been a war between, shall we say, street ballad and politically expedient and distracting spectacle, I mean, well, here's an older picture, that shows that even two hundred years before George W. Bush's crusade against the Democratic Party in Iraq it was going badly:

Bankelsang

Daniel Chodowiecki, The Improvement of Manners, 1786

The modern world, folks, had already begun.

Writers are not exactly getting good press here, either.

A writer writing on the back of a boy in a compromising position.

Nope, even in the 18th century, the tradition was not being taken seriously anymore. The 'peasants' are still mesmerized by the 'swashbuckling' singers, of course, yet just in case you missed it, in the background the modern world is beginning: a man falling out of a balloon painted as the world, on fire, someone else falling out of Juliet's tower, a soldier from the Napoleonic era patrolling the edges of the scene,

a naked ...man? woman? doing a somersault,

and devils in the border, thumbing their noses, too.

And who is that short little guy in the toga up front? He looks a bit like someone we may have seen before.

Is this Socrates?

I dunno. It looks like he has eyes in the back of his head. No, no, that’s not it: his head is screwed on backwards.

Sheesh.

Compare for yourself. Here he is with a stonier pose.

Socrates with his head screwed on properly.

So, let's screw our heads on properly, too, and not look out of the etching to see who is etching us, shall we.

And let's take it one step at a time.

What if that?

Would a poetry book today, then, be like this?

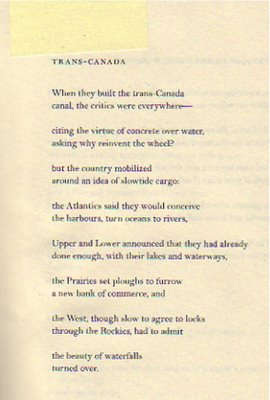

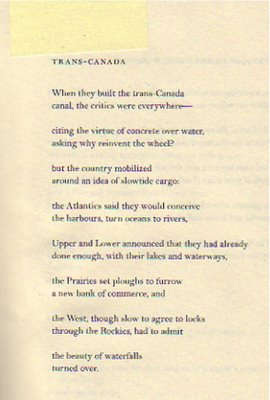

Matthew Holmes’ origami: Trans Canada

Map for the construction of the Northwest Passage

complete with Post It Note.

It has all the requisite parts, straight out of the shipping department at the canlit warehouses:

loose but effective prose rhythms, like a pallet of cardboard boxes being loaded on a truck, an effective minimalist slide of the rhetorical pattern against the alternate pattern set up by the silences created by the poem’s spine, fine self-referential but nonetheless humble humour, and a nod to Stan Rogers and the Fraser running home to the sea.

Which is perhaps the quintessential Canadian poetic theme: Guess what? Wherever you started out and wherever you're going, you're already there.

And no one could ever argue that Stan Rogers, or his brother Garnet, aren't of the people.

I mean, Garnet recently played in Riske Creek.

The Chilcotin Lodge, Riske Creek, 1944

Sitting on the edge of the B.C. Interior Grasslands, it hasn't changed in all the intervening years.

It's the kind of place that Garnet Rogers has been playing in this season.

Or would it be like this?

Blackbirds sitting in a tuning fork in the spring, imitating a poem by Matthew Holmes.

Kokanee Bay, Lac La Hache, April 2006

Or both?

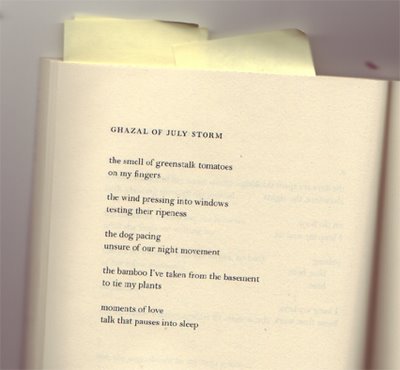

Such as this one:

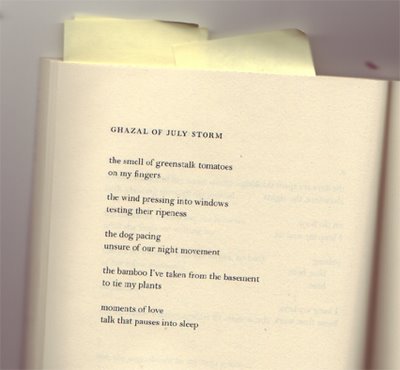

Matthew Holmes' Ghazal of July Storm

Where on earth does such mastery of the interface between prose and poetic language come from? Canada, sure, Matthew Holmes, sure, but what is it about Canada that has given rise to it?

Ah, this, I would think:

Poetry On the Straight and Narrow

Translating a Beetle-killed Lodgepole Pine Tree into stanzas

150 Mile House

July, 2006

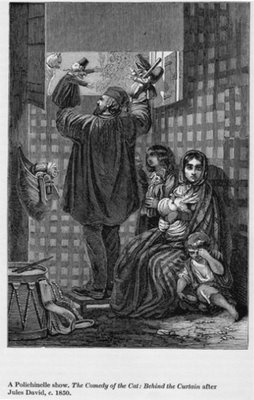

Back in the heydays of street ballads, some performers felt it was better to take their family behind a screen and show the little puppets of your mind, acting out the parts through a window, like the little window of light at the top of a dungeon, through which your soul could escape, leaving your body behind, or like Juliet’s window on her tower, with Romeo toking on his asthma inhaler in the rose bushes below.

In other words, not the aristocracy, installed by the Pope, God's scrying bowl on earth, but the puppeteer, the representative of a gnostic adept, who saw out of the darkness to a greater light, got to play God, and got to bring the wooden puppets to life.

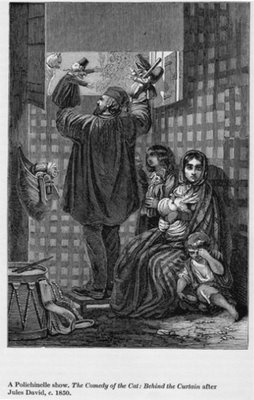

Performance as Political and Sacramental Subterfuge:

a Performance of Punchinello in Italy, c. 1850

Life and society might have been a prison, but there were ways around it.

I mean, if the world's a dungeon, what, exactly do we see out the window?

The View on the Lip of Paradise

That was, of course, a different age of the world. The Wild Man, the Sasquatch of the forests west of the Urals, a fellow believed by many to have been extant in Europe, and especially Germany, from before the incursions by the Romans and the Christians, had been used for a long time to give legitimacy to the Coats of Arms of noble houses from one end of Europe to the other.

Taming the Wild Man, or:

How to Become Civilized by Suppressing the Other, Humanizing Nature, and, in true Schizophrenic Fashion that would do even British Columbia politcs proud, Dehumanizing the Peasantry

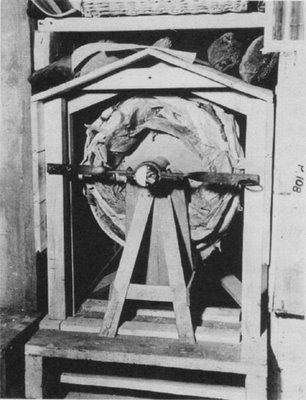

Some time after that, in Brecht's age, shall we say, in the age in which men first contemplated turning into machines, art was already dead — dead, yes, dead and severed from the contexts in which it had a political and social life, dead and turned into aesthetic objects, but still so recently dead and so recently anaestheticized that it was still revered as a badge of sophistication, even by its murderers and their willing henchmen. Witness:

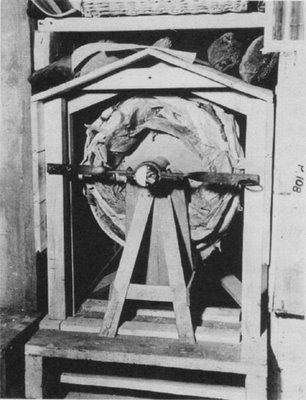

Rembrandt’s 'The Nightwatch' rolled up for transport,

after being stolen by the Nazis in World War II.

Ah, those Nazis, they were acting just like an anthropologist coming to the west coast of Canada in the 19th century and buying up all the treasures of a civilization. They expected that, soon enough, they alone would be the only heirs of the European tradition.

It was kind of an anthropological statement.

What does Holmes respond with? An aesthetic statement! He's going to come back out of the grocery store and pass us an apple that we can chaw down on while he packs the saddle bags and gets ready to ride out of town. Such daring!

But don’t kid yourself: art has a strong political role to play, especially in the minds of propagandists, who know very well the values people are willing to ascribe to it.

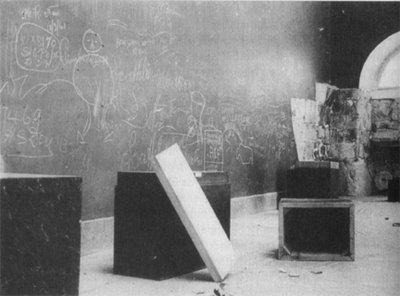

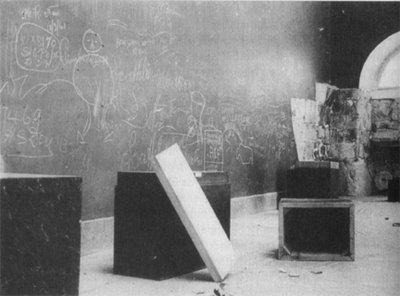

In World War II, for example, Italian propagandists distributed the following photograph of (absent, of course) stolen artworks and disrespectful graffitti in Cyrene, left by the American Army.

Oh, Those Barbarian Americans!

Sigh. Only the graffiti was real.

The giveaway? Why, the artfully arranged white slab and the darkness of the empty stand. Just too perfect. Those Italians! Even the propagandists can’t help turning out aesthetically beautiful work.

And the funny thing? It just wouldn’t look the same if it were true.

But what are you going to do? Take them to court? In Canada?

Why, here’s the courthouse in 150 Mile House, B.C. How about there?

150 Mile House, Courthouse,

British Columbia Interior, February 2006

Moved out of the way to widen the highway, it stands waiting to pass judgement.

Sorry, but in the interests of efficiency, the anteroom had to go.

Notice the effects of global warming.

No, there’s no room in Canada for such historical niceties.

Still, there is room for sending them up in style, for embodying all the contradictions at the end of one civilization and the beginning of another.

Or at least a bunch of them.

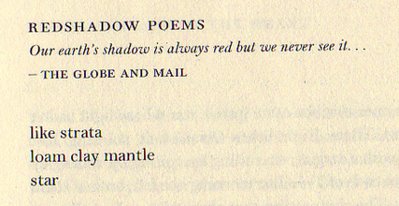

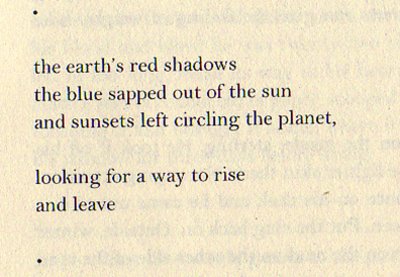

Such is Matthew Holmes’ Hitch. It’s a bit of a grab bag, as the blewointment genre demands: a few visuals, some lyrical poems, some prose poems laid out as lyrical poems, to walk on tippy toes through the minefields of their silences, some humour, a nod here and there to deconstructionist language poetry,

Matthew Holmes' Poem as Shopping List

a little bit of stuff which is just too earnest, because it actually believes its own rhetoric,

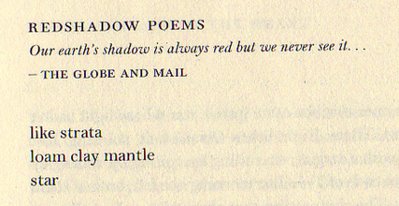

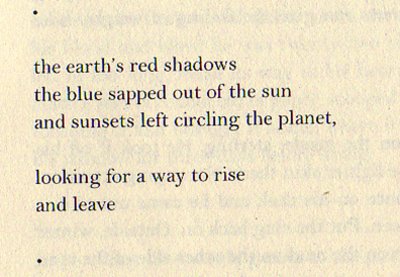

Redshadow Poems Again

Matthew Holmes’ Nod to Canlit

(Note to readers: Take the advice at this point and skip to the next poem),

and, hey, look at that, a sequence of prose poems that put Rimbaud to shame.

I'm not kidding. Only rarely does a poet pull off a prose poem anymore, but Holmes sure can.

“Smith’s Invisible Hand”, “Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle”, “Avogadro’s Law”, “Baeir’s Law [I and II]”, and “Starling’s Law of the Heart” are masterpieces of the form.

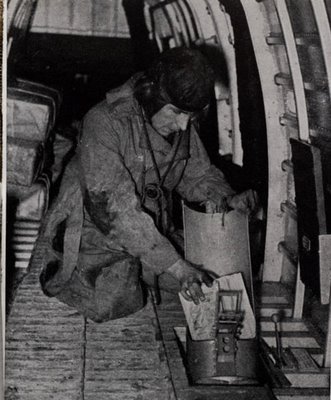

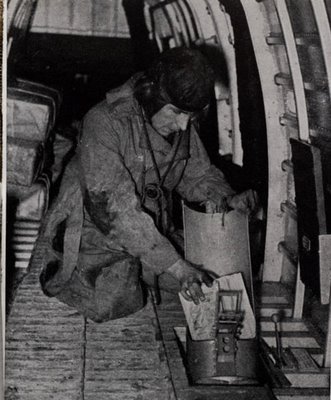

It sure beats trying to get the messge out this way, doesn’t it:

British Airman Dropping Propaganda Leaflets Over Nazi Germany

Notice the parcel post behind him, ready to go!

Well, ok, the prose poems might be Holmes' real strength, but the playfulness of the collection as a whole shows that Holmes has the ability to extend the prose poem into the conception of book, and to turn out highly-crafted, constantly inventive and refractive books of poetry, prose, lyrical, and walking the edge between them.

I mean, there lies as potential within Hitch the book of prose poems, the book of Redshadow Poems (So far, all we have are the notes), the book of ghazals, the book of canal poems, the book of...

I for one, look forward to watching Holmes follow all these seeds and extend them as the foundations for a 21st Century Canadian poetry that understands the past in all its compromised positions and successfully evades the lures of materialism and aestheticism.

There is still hope that we will remain a people.

History, it seems, must repeat itself.

So, in true Canadian fashion:

Tolko Lumber Company Driveway Stop and Go Sign

Formerly the Ministry of Forests

Williams Lake, B.C.

November, 2006

It must be the result of global warming.

*

Coming Soon: Penn Kemp, Jen Currin

The text of this article is copyright Harold Rhenisch, 2006. All rights reserved.

Hitch.Nightwood Editions, 2006, 96 pp., $16.95

A fine example of an early 21st century technical writing manual,

with close-up diagram showing the procedure for linking the nerves to the spinal cord.

(Optometrist’s Note: This is the version put out for public show by the publisher. The physical-interface version is conveniently larger, for interface with Anthropological OS1.)

Highlights of the Canadian anti-book tradition include the Gestettner of the TISH poets in 1963 Vancouver, the purposefully badly photocopied and/or elegantly designed poetry books of the anarchist tradition of the Toronto Small Press Book Fair, and mail artists bent on distributing work without either art or a book.

The sleight of mind that can even conceive of such a challenge is the very definition of being Canadian — living as we do in a country that prefers to read books from other countries and has few places to sell those from our own, and all in all sees this as the ultimate in sophistication.

Oh, wait. That's not Canada. That’s almost everyone.

A little evidence to that effect:

Some writers have so confounded society with government, as to

leave little or no distinction between them; whereas they are not

only different, but have different origins ... Society is in

every state a blessing, but Government, even in its best state,

is but a necessary evil; in its worst state, an intolerable one.

--Thomas Paine,

Common Sense, 1776

Barlow's (and Holmes') kind of publishing as the true act of a free man has, it seems, a long history.

throwing what looks like a Paper Airplane... or, damn it, isn't that a California Quail?

(Fashion note: not a bad outfit for a man who died a pauper, eh.

Household budgeting note: One can see why.

Photographic composition note: a flagpole in his back pocket? It breaks the rules, yet it works!)

I suspect that what Paine had in mind with his title, Common Sense is not what we necessarily mean by it today, as something reasonable and obvious to all men without the application or corruption of intellect, but something akin to Common Law, as in from the people, not from their lords and masters.

Now we use it to describe the cohabitation of a man and a woman with the sanctifying blessings of (and obligations to) the Church. Nice!

Other definitions of the essence of being Canadian:

A Canadian knows how to make love in a canoe. Pierre Burton

A Canadian loves hockey. Peter Gzowski

Canadians say "Sorry!" way too much. Everyone else in the world.

Oh dear. But, you know, meaning is a slippery business, after all. You just can never nail it down to one thing or another. I mean, like all good books, of course, even Paine's Common Sense had earlier drafts. Here's a sample of one of its earlier evolutions:

(Fashion note: notice the Hungarian Hussar's plume!)

Oh, wait, Thomas Paine, American patriot, was an anarchist? The United States is an Anarchist society? The United States is in favour of extra-marital cohabitation?

Well, well, well, leaving aside the notion that Canadian anarchist publishing was American-inspired, anarchist publishing was the kind of thing that in the 1960s gave us Canadian literature as we know it today, with the gliterati at the Gillers in all their new dresses and black suits and the writers sitting around in their v-neck sweaters wondering what they are doing there. Back then it was just samizdat.

Illegal books, illegally typed by hand, and illegally distributed in Cold War Eastern Europe. The kind of thing that could get you hurled into the Gulag.

You ever wondered what happened to samizdat? Simple. The American version has become a point of pilgrimage for the tourists of Revolution.

Abbreviated for instantaneous transmission along the imagistic cortex

An example of American Anarchist Post-Gutenberg Publishing.

(Anarchist’s Helpful Note: Maybe you can melt a book like this down into shell casings, but burning it is simply out of the question.)

The Soviet version has become a point of pilgrimage for the tourists of Revolution.

Samizdat museum in the former Soviet Union.

What was forbidden is now a shrine.

Crowded, too!

(Note for Pilgrims: follow the Light at the End of the Tunnel)

In fact, Sono Nis Press even did a series of samizdat books back in 1971: imitations of the books privately printed on typewriters and passed out by hand at great peril in Soviet Europe.

For the most part, the poets published in the series were graduates of the Creative Writing Department at the University of British Columbia, back in the days when the department was not the establishment, but was trying to throw paper airplanes over its walls.

One of Sono Nis Press's Samizdat Poetry Series

Check out the funky retro courier font, typed on a typewriter for sure, in Andreas Schroeder's version, file of uncertainties below. Just the perfect thing for Matthew Holmes, what with all the tricky rope work and all.

In the Soviet Union, of course, publishing in samizdat could get you into the Gulag. And back in non-aligned British Columbia? What about that? Back in the days when the entire Hungarian forestry department was ensconced at the University of British Columbia?

Na. The peril wasn’t there. I mean, these were poets, sure, so they were rather unwanted social accidents, granted, but they were British Columbian poets, which is to say they felt like they were on the right side of the Rockies, and they were Canadian poets, which is to say they were just as good as creating virtual realities for themselves as they were at writing poetry.

Here's a piece of virtual reality from another and very distant Canadian coast, from New Brunswick:

for the re-creation of the world of Matthew Holmes inside your head,

from Owl Shaped in Reeds

Hey, what's that peeking in from the other side? Check it out.

Useful, too!

(Note for Travellers: It remains unclear whether these rooms come with private bath,

or whether you have to share the w.c. down the hall.)

See what I mean? Mail art between covers. Absolutely everything is in there. It seems to be Holmes' desire that they all cohabit in there.

How common!

Back in the 1960s, everyone was getting in on this act. Fiddlehead Books in Fredericton, New Brunswick, just published everyone who sent them a manuscript. So did bill bissett's blewointment press in Vancouver. He rejected no one. Of his writing in that time, bill says that he was trying to change the world. And, sure, production standards in this genre were, well, low, but the craziness of the environment was invigorating. Invigorating is good.

published by Fiddlehead Books in 1973.

What is it? Pretty hard to say, actually, but the idea of breaking the surface of poetry, to relegate images to photography and to sit outside of them, was ahead of its time. And certainly ahead of photocopy technology.

Then came canlit.

IKEA moved into the country and sold knockdown beds cheap.

Time passed.

Past time came again.

Past time passed.

Everyone forgot everything. Everyone slept in.

People, understandably enough, started to get pissed.

Starbucks came onto the Canadian scene, to wake everyone up.

Then all the writers of Vancouver started to haul their laptops to Starbucks and write from there, so they could get away from it all and (in a writerly way, of course) rub shoulders with people.

Then Matthew Holmes started to send out his messages, in code, to show there was still life out there. You know, it's nice to see the original craziness honoured in Matthew Holmes’ first book of poetry, Hitch, put out by the resurrected Blewointment Press and made to look like something run off on a photocopier that somehow learned how to print beautifully, full of objects made to look like poems, and presented as a combined guide to semaphore and knot-making.

from Traditional Dances for Tourists

Notice how the knots are in the rope that is the silence between the iterations of the sound that is the nod to the poems of the past.

Don’t you love the random static coming through from the transmissions on the other side of the paper, from the future, so to speak?

A nice nod to Fiddlehead, don't you think?

Oh. Hitch comes with a warning, though: if you squoosh it down too long in your scanner and hold down the lid, the pages will never close again. Yeah, I know. Everyone's using cheaper paper these days.he

Pretty soon, poetry will have folded itself down into origami.

It's like listening to something by the American composer of silence, John Cage, or by the Canadian composer of solitude, Glen Gould.

cueing up on the bars for a performance of Glenn Gould's Solitude Trilogy, now that the composer has gone back to the elements. November 12, 2006. Lest we forget.

Of course, all these nods to the past, all this mail art and powerline art, has to have a root somewhere, in more than the question, saucily put: Which came first? The blackbird or the egg?

Well, forget about making love in a canoe. A modern street balladeer is someone who knows how to wear armour. In some cases, it might be furnace ducting.

to read a nonsense poem in Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich in 1916,

while WWI was raging not all so far away.

Expecting tomatoes, are you, Hugo?

In other cases, it might just be the covers of a book.

Hitch: to hook a tent trailer to your bumper and take the kids to the lake for the weekend; to tie the knot before the altar, wearing a suit that is not going to fit you in ten years, believe it (As opposed to living commong law), to tie up your Al Purdy to the railing in front of the general store, while you go in for some groceries; not to mention clove hitch, half hitch and other specialized knots that hold only when the rope is under tension.

Want to get away? Just let the pressure go.

Come on, let it go. Breathe in. Breathe out. Ahhhhhhhh. Feels good, huh? Remember:

To attempt and "re-live" old and long gone moments of glory and joy is already in the hard world of physical objects a true nightmare, but on the energy levels it is the greatest catastrophe, for it turns our forward flowing timelines into the equivalent of a Gordian knot, a Minotaur labyrinth in which people get lost altogether, with no hope of finding an exit, with no hope of escape, ever.

Sylvia Harman. The Enchanted World.

Matthew Holmes lets the pressure go, but it's a sly sleight of hand, built on humour. Hugo Ball didn't mind a little bit of humour, either. Just getting up in front of a crowd was funny enough for him.

You see, both Hugo and Mathew stand at the end of a long tradition of street balladeers. Well, past the end, actually, because, really, they can only reference something that has gone. There just aren't any street balladeers anymore.

That's what we have the magazine racks at the grocery store for, come on.

No poets, either, actually.

But, here's the miracle: I once ran into one in Toronto. The year was 1998. The summer was hot and muggy. He had a tray strapped in front of himself and was selling poetry: USED DOG URINE.

Well, that's what his sign said. The poems were photocopied on bright, yellow paper.

It was like seeing a Great Auk.

Kind of the Canadian equivalent of this English Dude:

Hmm... don't you think he looks a bit like Robert Graves?

The damn stuff will kill you in the end.

Graves ran his own printing press, too, but that was on Mallorca, where he had gone to put England behind him, and where he published beautiful, artistic volumes of poetry for an elite market.

Kind of like this:

Hitch Yourself to Hitch Right Here Today.

Except, of course, this isn't Mallorca, it’s Canada, in 2006, which means that, in the true schizophrenia of Canadian society, playing the cute American game of privileged elites pretending to be defending the rights of common law, while Matthew is trying to remake 1967, other people are trying to remake this:

That’s the context Matthew Holmes is writing in. Everything you learned (or experienced) about the development of society in the 20th Century? About the bloody battles that eventually handed power to the people from aristocratic and intellectual elites?

Well, that’s over.

It just doesn’t apply any more. All we have are ruins, and in those ruins, young poets like Holmes are left trying to create a world, a poetic, out of the shards. It’s all shards. Everywhere you look, there are shards: shards of sestinas and shards of sonnets, shards of language poetry and shards of visual poetry, shards of modernist free verse and shards of Gray’s Elegy on a Country Churchyard, all smashed up and lying somewhere on the tundra. The gig is up. The poetry is over. Now we have Canlit. Now we have Carmine Starnino railing against Canlit, in this 'art' learned at school.

Whereas the real poetry was meant to act upon the world. Kind of like this.

See what I mean?

The thing about reality is that it doesn't exist anymore. It, too, went the way of the Great Auk. The thing about street ballads is that they were the refuge of the working class. This was their art. Silencing them was more than an aesthetic statement.

It was politics.

So, how on earth, then, did some of it survive for Matthew to reference and within the context of poetry-as-an-aesthetic-object write a virtual street poet experience?

How did such a fragile thing survive, so late past history, for him to nod to, and how did there survive enough readers familiar enough with the weaker points of the new genre to get his joke?

Well, let me suggest it was these guys who smuggled it through:

That’s the playwright Bertolt Brecht, second from the left.

Brecht went on to use his art for political ends, as agit prop for communism. Nice picture of Hitler up on the wall, too! And is that Stalin the circus strong man being run over by the cart? And I’d love to know what they had in mind for the balls. Bowling, perhaps?

Dramatists, eh!

The poets might have been complicit with modernism, but the dramatists were not. In fact, they were trying for a little bit of improvisation, gently and not-so-gently testing and probing their audiences. Here is one of the twentieth century's greatest dramatists:

(Note to Conspiracy Buffs: Notice how he is losing his head in his role)

Stalin was really keen on spectacle and on audience participation. It was his aesthetic stance that the audience members were, in themselves, nothing, that the individual human experience was an illusion. Collective experience, the experience of an audience also playing the roles, was all. The brutality that can come out of such an aesthetic has, of course, caused it to have some pretty nasty reviews. After all, it's not the job of a playwright to enslave or even kill his audiences, but to hound them out of the theatre and into the streets.

Where, of course, society forbade them to sing their ballads.

Nowadays, a strong man is someone you blow up with hot air.

I think Brecht would have liked that.

Circus strongman as an advertising gimic.

The tradition of a free peasant class, untramelled by art, was, however, not doing very well in Brecht's time, either, in the 1920s when the picture of his comedy troupe was taken, but had far, far older roots. If history has been a war between, shall we say, street ballad and politically expedient and distracting spectacle, I mean, well, here's an older picture, that shows that even two hundred years before George W. Bush's crusade against the Democratic Party in Iraq it was going badly:

Daniel Chodowiecki, The Improvement of Manners, 1786

A Bänkelsänger, a German street balladeer, points to a board, on which thirteen representations of human happiness, misery and criminality can be made out.

A piece of political satire, for sure. Notice how the traditional fertility god's goat foot has been replaced by an amputated leg, and the peasant bankelsingers have ben replaced by Renaissance soldiers in Spanish Dress and how the peasants in the audience don't, well, don't look exactly impoverished, do they.

The modern world, folks, had already begun.

Writers are not exactly getting good press here, either.

Nope, even in the 18th century, the tradition was not being taken seriously anymore. The 'peasants' are still mesmerized by the 'swashbuckling' singers, of course, yet just in case you missed it, in the background the modern world is beginning: a man falling out of a balloon painted as the world, on fire, someone else falling out of Juliet's tower, a soldier from the Napoleonic era patrolling the edges of the scene,

and devils in the border, thumbing their noses, too.

And who is that short little guy in the toga up front? He looks a bit like someone we may have seen before.

I dunno. It looks like he has eyes in the back of his head. No, no, that’s not it: his head is screwed on backwards.

My advice to you is get married: if you find a good wife you'll be happy; if not, you'll become a philosopher.Socrates

Sheesh.

Compare for yourself. Here he is with a stonier pose.

So, let's screw our heads on properly, too, and not look out of the etching to see who is etching us, shall we.

And let's take it one step at a time.

1. If the street ballad tradition these days is referencing the street ballad tradition,

2. but not continuing it, and if

3. poetry has gone the way of the fletcher's workshop, and,

4. if poetry has been trying to become an image for a century,

5. what if it had actually worked, and it’s now the natural world that lies outside the corridors of power and plays music?

6. What if the early modernist poets were actually successful and almost everything we knew as literature today was reactionary, counter-revolutionary spin?

What if that?

Would a poetry book today, then, be like this?

Map for the construction of the Northwest Passage

complete with Post It Note.

It has all the requisite parts, straight out of the shipping department at the canlit warehouses:

loose but effective prose rhythms, like a pallet of cardboard boxes being loaded on a truck, an effective minimalist slide of the rhetorical pattern against the alternate pattern set up by the silences created by the poem’s spine, fine self-referential but nonetheless humble humour, and a nod to Stan Rogers and the Fraser running home to the sea.

Which is perhaps the quintessential Canadian poetic theme: Guess what? Wherever you started out and wherever you're going, you're already there.

And no one could ever argue that Stan Rogers, or his brother Garnet, aren't of the people.

I mean, Garnet recently played in Riske Creek.

Sitting on the edge of the B.C. Interior Grasslands, it hasn't changed in all the intervening years.

It's the kind of place that Garnet Rogers has been playing in this season.

Or would it be like this?

Kokanee Bay, Lac La Hache, April 2006

Or both?

Such as this one:

Again, the nod at the end to silence, but, again, the fine Canadian use of the echoes of lyrical linebreaks, within prose rhythms, to create the framework that will support it.

(Note to Studio Audience: Applaud here!)

Where on earth does such mastery of the interface between prose and poetic language come from? Canada, sure, Matthew Holmes, sure, but what is it about Canada that has given rise to it?

Ah, this, I would think:

Translating a Beetle-killed Lodgepole Pine Tree into stanzas

150 Mile House

July, 2006

Back in the heydays of street ballads, some performers felt it was better to take their family behind a screen and show the little puppets of your mind, acting out the parts through a window, like the little window of light at the top of a dungeon, through which your soul could escape, leaving your body behind, or like Juliet’s window on her tower, with Romeo toking on his asthma inhaler in the rose bushes below.

In other words, not the aristocracy, installed by the Pope, God's scrying bowl on earth, but the puppeteer, the representative of a gnostic adept, who saw out of the darkness to a greater light, got to play God, and got to bring the wooden puppets to life.

a Performance of Punchinello in Italy, c. 1850

Life and society might have been a prison, but there were ways around it.

I mean, if the world's a dungeon, what, exactly do we see out the window?

1. The sphinx, 2. the Wild Man (who gets to make the landscape) and 3. Punch. The only bit of any kind of a natural world out there is a dead tree sticking out of the Wild Man's nose.

That was, of course, a different age of the world. The Wild Man, the Sasquatch of the forests west of the Urals, a fellow believed by many to have been extant in Europe, and especially Germany, from before the incursions by the Romans and the Christians, had been used for a long time to give legitimacy to the Coats of Arms of noble houses from one end of Europe to the other.

How to Become Civilized by Suppressing the Other, Humanizing Nature, and, in true Schizophrenic Fashion that would do even British Columbia politcs proud, Dehumanizing the Peasantry

Some time after that, in Brecht's age, shall we say, in the age in which men first contemplated turning into machines, art was already dead — dead, yes, dead and severed from the contexts in which it had a political and social life, dead and turned into aesthetic objects, but still so recently dead and so recently anaestheticized that it was still revered as a badge of sophistication, even by its murderers and their willing henchmen. Witness:

after being stolen by the Nazis in World War II.

Ah, those Nazis, they were acting just like an anthropologist coming to the west coast of Canada in the 19th century and buying up all the treasures of a civilization. They expected that, soon enough, they alone would be the only heirs of the European tradition.

It was kind of an anthropological statement.

What does Holmes respond with? An aesthetic statement! He's going to come back out of the grocery store and pass us an apple that we can chaw down on while he packs the saddle bags and gets ready to ride out of town. Such daring!

But don’t kid yourself: art has a strong political role to play, especially in the minds of propagandists, who know very well the values people are willing to ascribe to it.

In World War II, for example, Italian propagandists distributed the following photograph of (absent, of course) stolen artworks and disrespectful graffitti in Cyrene, left by the American Army.

Sigh. Only the graffiti was real.

The giveaway? Why, the artfully arranged white slab and the darkness of the empty stand. Just too perfect. Those Italians! Even the propagandists can’t help turning out aesthetically beautiful work.

And the funny thing? It just wouldn’t look the same if it were true.

But what are you going to do? Take them to court? In Canada?

Why, here’s the courthouse in 150 Mile House, B.C. How about there?

British Columbia Interior, February 2006

Moved out of the way to widen the highway, it stands waiting to pass judgement.

Sorry, but in the interests of efficiency, the anteroom had to go.

Notice the effects of global warming.

No, there’s no room in Canada for such historical niceties.

Still, there is room for sending them up in style, for embodying all the contradictions at the end of one civilization and the beginning of another.

Or at least a bunch of them.

Such is Matthew Holmes’ Hitch. It’s a bit of a grab bag, as the blewointment genre demands: a few visuals, some lyrical poems, some prose poems laid out as lyrical poems, to walk on tippy toes through the minefields of their silences, some humour, a nod here and there to deconstructionist language poetry,

a little bit of stuff which is just too earnest, because it actually believes its own rhetoric,

Matthew Holmes’ Nod to Canlit

(Note to readers: Take the advice at this point and skip to the next poem),

and, hey, look at that, a sequence of prose poems that put Rimbaud to shame.

I'm not kidding. Only rarely does a poet pull off a prose poem anymore, but Holmes sure can.

“Smith’s Invisible Hand”, “Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle”, “Avogadro’s Law”, “Baeir’s Law [I and II]”, and “Starling’s Law of the Heart” are masterpieces of the form.

It sure beats trying to get the messge out this way, doesn’t it:

Notice the parcel post behind him, ready to go!

Well, ok, the prose poems might be Holmes' real strength, but the playfulness of the collection as a whole shows that Holmes has the ability to extend the prose poem into the conception of book, and to turn out highly-crafted, constantly inventive and refractive books of poetry, prose, lyrical, and walking the edge between them.

I mean, there lies as potential within Hitch the book of prose poems, the book of Redshadow Poems (So far, all we have are the notes), the book of ghazals, the book of canal poems, the book of...

I for one, look forward to watching Holmes follow all these seeds and extend them as the foundations for a 21st Century Canadian poetry that understands the past in all its compromised positions and successfully evades the lures of materialism and aestheticism.

There is still hope that we will remain a people.

Adam (dressed as Wild Man): Ha ha ha!

Harold: Ha ha ha, yourself. Say, don’t I know you from somewhere?

Adam: Ha ha ha!

Harold: The nakedness, certainly, but it’s something else.

Eve (Giggling.): Guess!

Harold (Understanding at last.): Oh, you guys. You had me on there.

Adam: That we will become one. Did you get it?

Harold: Get what?

Eve: That we will become a people!

History, it seems, must repeat itself.

So, in true Canadian fashion:

Formerly the Ministry of Forests

Williams Lake, B.C.

November, 2006

It must be the result of global warming.

*

Coming Soon: Penn Kemp, Jen Currin

The text of this article is copyright Harold Rhenisch, 2006. All rights reserved.